Currently on display at The Luminary on Cherokee Street, Moving Stories in the Making is an exhibition of migrant narratives, as rendered by a diverse group of local and national artists.

Conceived and organized by Moving Stories, a programmatic grant of the Incubator for Transdisciplinary Futures, the installation lasts until March 30. One of the featured artists, the Peruvian-born Rafael Soldi, will visit the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts for a guest lecture on Friday, March 22.

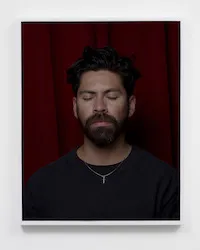

Ahead of his visit, we asked Soldi to walk us through the inspirations that sparked his contribution to Moving Stories, Entre Hermanos. The piece features a contemplative series of portraits of male-identifying queer Latinx immigrants, photographed with their eyes closed in a moment of meditation. This work serves as a spiritual successor to Soldi's self-portrait series, Imagined Futures.

"The work aims to ask, how do we grieve the life we left behind in order to live this one?" Soldi wrote of Imagined Futures. "What do we, immigrants, do with these collective haunting visions and questions about the lives we left behind?"

I'd like to start with your own immigration story, as that feels like the bedrock beneath both Imagined Futures and Entre Hermanos. Where were you in life when you emigrated to the United States? How did the move disrupt your life and the life you'd imagined for yourself? What did you have to leave behind?

I moved to the United States from Lima, Perú, when I was 15 years old. It was an odd time to immigrate. On one hand, it was incredibly difficult to leave my life, my friends, and my social circles behind at a time when those things felt so important. I just had two years left of high school and I had attended school with that exact cohort since the first grade. Everything was upside down, I missed home a lot, and because we moved in February, I couldn't start school until August, so it would be almost 6 months before I could make new friends.

On the other hand, I was increasingly aware of my queer identity, and I had always had a fraught relationship with the institutions that raised me, such as my Catholic school, and never quite felt like I fit in with my peers. Perú was/is a very conservative country, as well as homophobic, sexist, racist, classist, and very religious. It took a little while but I eventually understood this journey as an opportunity to start a new life, to build something that would better suit my identity. But I left behind a lot of questions, a complicated relationship to a place I still love, of which I'm very proud, and at the same time a place in which I struggled a lot. I took with me a lot of questions about what life could have been like had I not had the opportunity to immigrate.

From those experiences, what inspired the particular aesthetic and approach of Imagined Futures? I imagine a deeply personal project like this swirls around in your head for a great period of time before you find the ideal vehicle for expressing it. How did creating these self-portraits help to process your own journey as both an immigrant and a queer person?

Arriving at the final work was a slow process of discovery that unfolded in waves. This body of work was a turning point for my practice on a few levels. For starters, feeling ready to unpack this complex relationship—to my country, to immigration, to unanswered questions, to futurity—was revelatory for me. What followed was a bit of a crisis of medium, formally speaking. I had been trained as a photographer in a very traditional sense, and the questions here felt abstract in a way that I couldn't address through "straight photography." The swirling qualities of questions called for the formal layering that eventually ensued—the performance and ritual elements, the choice of medium and place/placeness of the work, the repetition and installation elements, and the historical referencing of the photo booth.

The process of making this work, especially its repetitive nature, was healing and powerful in the journey to understanding and unpacking my queer and immigrant identity. The more powerful part, however, was the period that followed the exhibiting of the work. The conversations I continue to have with people, the questions I am asked that challenge me to think through complex ideas, and especially the kinship with fellow immigrants who see their experience mirrored in mine.

How did you and collaborator Joel Aguirre develop Entre Hermanos, the piece currently on display at The Luminary? Here you're taking the premise of Imagined Futures but expanding it outward into representing a fuller community of queer Latinx immigrants. What inspired this new iteration? How did you identify the subjects?

I got in touch with Entre Hermanos, a non-profit organization in Seattle providing social, educational, and health support services to the Latinx community since the dawn of the AIDS epidemic. I collaborated with Joel Aguirre, a staff member who works closely with the community and whose drag persona, La Gordis, performs all around town. Joel gathered a group of men from the community, whom you see pictured in the work in the exhibition. We met for several hours, I shared my work with them and went over the questions that I aimed to answer in the making of the work. We then used these questions as a starting point for our conversation. Each person shared their own experiences of immigration, or navigating their identities early in life, of the role of imagination for them as they pictured a future as children in their motherlands. We discussed what is at stake as we build new lives, what we've sacrificed and what we've gained.

At the end of the conversation, I invited each one for a private moment inside a photo booth that I built. I asked each to close their eyes and contemplate, within themselves, a series of questions and meditations I read out loud. They each held the cable release, and were instructed to make a self-portrait, if desired, at any time during the process. The resulting images were made by them, of themselves, at their chosen moment.

They exist as evidence of that moment, as documentation of a deliberate effort to make peace with the grief that saturates the experience of leaving your home to save yourself, to embody yourself fully.